Input | Run Ahead

Run-ahead is the name for a very interesting technique that can be used to remove the internal processing delays in emulated video games, resulting in input lag reductions of entire frames: 16ms per frame with NTSC, and 20ms per frame with PAL video. Combined with an optimal PC configuration, it becomes possible to achieve lower latency on a software emulator running on a PC than is possible on real-hardware using a CRT!

Overview

Imagine you’re playing Mega Man X, and you press the jump button to make the protagonist X jump into the air. In an ideal world, the very instant the jump button was pressed down, you would see X begin to jump. But the game actually needs time to make this happen, it must:

- • poll the controller and see that the jump button is pressed,

- • update the player sprites in memory,

- • scroll the background layers if necessary,

- • begin playing any sound effects to signal the action, and

- • redraw the screen in the updated position

Depending on the game in question, this usually takes between one to four frames to happen. A large source of the latency is that games only poll the input states once per video frame during their vertical blanking interrupts.

The goal of run-ahead is to skip over these idle frames using time-shifting:

As you can see, Mega Man X requires three frames between pressing the jump button and seeing X begin to jump. This means there’s an internal processing delay of two frames before our desired third frame is drawn. As such, a run-ahead setting of 1 skips over one of these frames, and a setting of 2 skips over both of these two delay frames.

Now what happens when we skip over three or more frames is we begin to skip over the starting animation frames, which leads to a very unpleasant rubber-banding visual effect.

You’ll understand why as I explain how run-ahead works. But for now, I’d like to stress that virtually every single Super Nintendo game has at least one frame of internal processing delays, and so a setting of 1 works for all but maybe 0.1% of the library. The higher the run-ahead, the less compatible it becomes, but generally a setting of 1 is a set-it and forget-it affair.

As such, run-ahead is a technique to shave off 16-20ms of input latency in nearly the entire SNES library. And the same likely holds true for most other systems one might wish to emulate.

Technical Explanation

As mentioned above, run-ahead is a time-shifting technique. Let’s first look at a standard emulator run loop:

void Emulator::runFrame() {

input.poll();

auto [videoFrame, audioFrames] = emulator.run();

video.output(videoFrame);

audio.output(audioFrames);

}

(Extra reading: this input polling strategy is sub-optimal. See my article on input latency reduction for a just-in-time polling technique that will shave an additional ~8-20ms of latency off input, which stacks on top of run-ahead’s latency reduction.)

Implementing run-ahead changes the run-loop like so:

void Emulator::runFrameAhead(unsigned int runAhead) {

if(runAhead == 0) return runFrame(); //sanity check

//poll the input states of the controller buttons

input.poll();

emulator.run();

//video and audio frames discarded (not sent to the monitor and speakers)

//capture the system state so that we can restore it later

auto saveState = emulator.serialize();

//we can run-ahead as many frames as we want

while(runAhead > 1) {

emulator.run();

//these frames are also discarded

runAhead--;

}

//here we run the final frame

auto [videoFrame, audioFrames] = emulator.run();

//the final frame is rendered

video.output(videoFrame);

audio.output(audioFrames);

//lastly, we restore the save state we saved earlier

emulator.unserialize(saveState);

}

Let’s say that runAhead = 2 here. What the above code does is poll the controller inputs, and then the next three frames are emulated. Only the third and final frame is displayed onscreen.

The purpose of the save state is so that even though we’ve run three frames, we load the previous state after running just one frame, thus maintaining a standard 60fps (NTSC) or 50fps (PAL) game speed rate.

Effectively, the result of runAhead = 2 is to show you what would have happened had you pressed or released a button on your gamepad two frames earlier.

Indeed, the technique works both on button presses and releases. And because we are always displaying a constant number of frames into the future, there is no video or audio distortion, so long as you do not exceed the number of internal processing frames the game naturally has.

When you exceed the number of internal processing delay frames, it begins to skip over the beginning animation sequences and start of sound effects, which is rather jarring. But again, a setting of runAhead = 1 basically works virtually everywhere, and is a very easy win.

Visual Demonstration

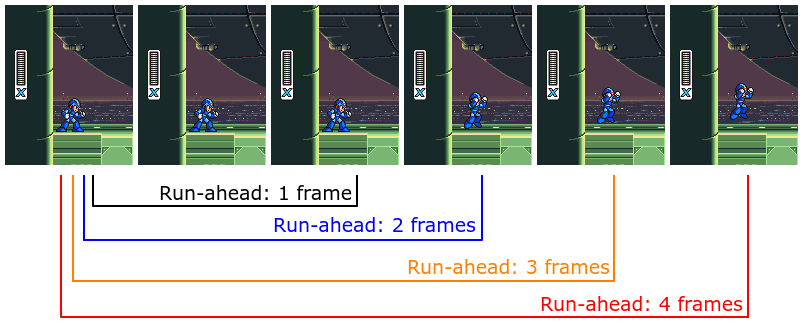

Here is an example where the X-axis represents the frame number (from 0-5), and the Y-axis represents the number of run-ahead frames (from 0-4.)

(Note: you may click or tap the images on this page to see them at full resolution.)

Imagine that the left-most frame (#0) represents the idle state, and immediately after said frame is drawn, you press the jump button. When run-ahead is set to zero (or in other words, no run-ahead is used), you can see that X does not begin to jump until three frames later.

Increasing run-ahead to 1 skips over the first idle frame, allowing X to begin his jump after only two frames.

Increasing run-ahead to 2 skips over both internal processing delay frames, allowing X to begin jumping immediately on the very next frame.

Increasing run-ahead to 3 goes too far for this specific game, and the first animation frame of X jumping is lost.

Increasing run-ahead to 4 skips over two animation frames.

Thus, for this specific game, a run-ahead setting of 2 safely reduces the input lag of X’s jump by 32ms in the NTSC version of this game, at no consequence.

Alternate Incorrect Visual Demonstration

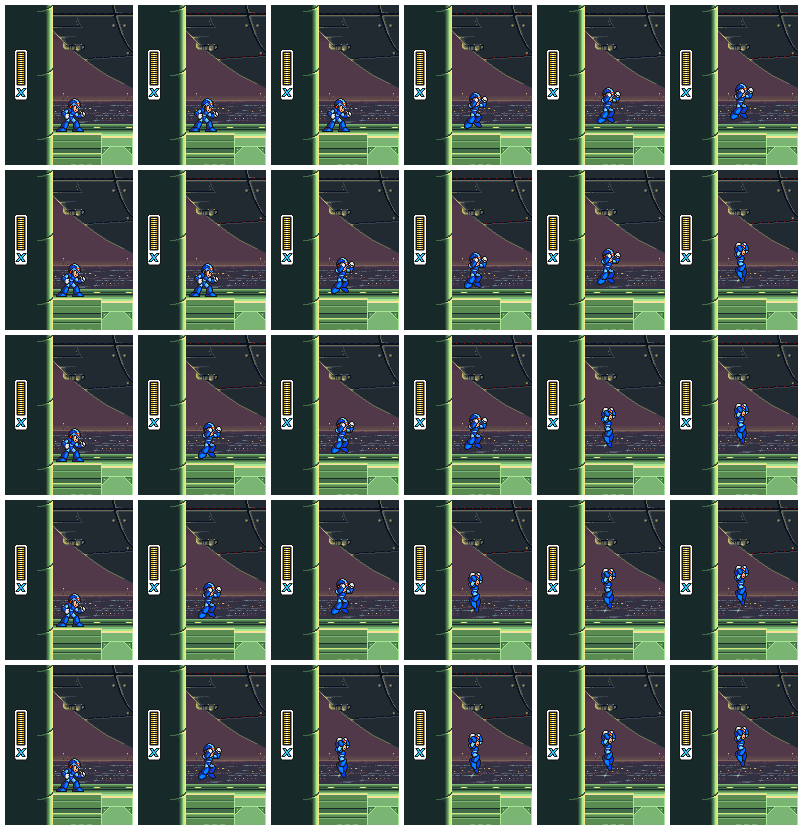

Another way to visualize the data is like so:

But this only serves as a more convenient visual aid, and is not technically what is happening with run-ahead. Remember that run-ahead is always running frames in the future, not only on input state transitions.

Alternate Correct Visual Demonstration

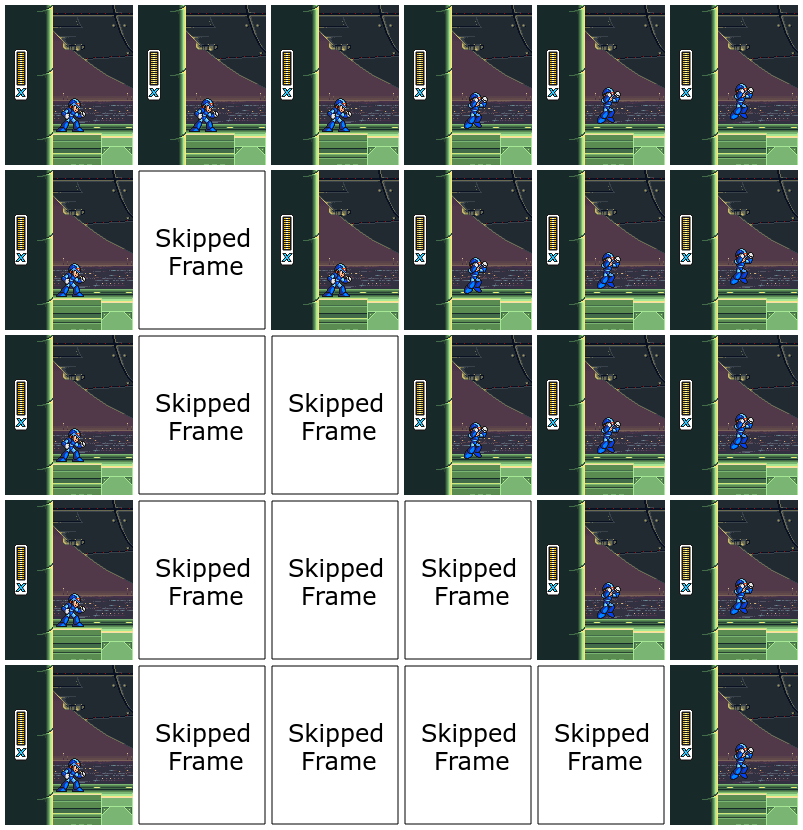

The actual result during gameplay is thusly:

The reason why X has not begun jumping sooner in the first rendered frame is because at this point we have not seen the jump button pressed on the controller, and as such, said input has not been sent back to be emulated yet.

So in the above corrected visual demonstration, the first visual frame has the jump button released, and all subsequent visual frames have the jump button pressed.

Overhead

This technique seems like a clear win, so what’s the catch? Mainly, just overhead. You cannot offload frame generation to a multi-core CPU, because each frame has to be rendered in-order, one at a time. In other words, it’s a serial process.

What this means is that for a run-ahead setting of 1, you have to emulate the entire Super Nintendo system twice. For a setting of 2, three times. And for a setting of 4, you have to run the Super Nintendo and generate a full five frames worth of video and audio data before outputting just one frame. This means that it has five times the overhead of running the emulator without run-ahead.

There are tricks that can be done to reduce the overhead: specifically, because the frames are not displayed onscreen, you do not have to emulate the video generation. In other words, you treat it similarly to frame-skipping. Since video is often one of the most expensive portions of emulation, this can greatly reduce the performance impact of run-ahead. In the case of bsnes, it means each frame of run-ahead only adds about 40% of additional overhead compared to another 100% of additional overhead.

Recent extensive optimizations to bsnes in particular allow it to easily handle even four frames of run-ahead on an entry-level Ryzen CPU, but of course your mileage may vary, and it depends upon how demanding your emulator is already.

(Note: when users use an emulator’s turbo function [running at uncapped framerates to speed through tedious portions of games], run-ahead should be disabled so that the emulator can hit its maximum frame rate still.)

Competitive Gaming

This raises an important question when it comes to the use of run-ahead in competitive gaming: is run-ahead cheating?

Reducing input latency will certainly give a skilled player an advantage.

In my view, as long as the use of run-ahead and the number of frames skipped is disclosed and consistent among all players, it becomes a fair playing field.

But it’s up to others to decide whether they view this as acceptable or cheating.

When it comes to solo, non-competitive playing, I really can’t see why it would matter, but to each their own of course. Run-ahead is just one more powerful option for people who are interested in reducing input latency in emulation.