Video | Color Emulation

Nearly all retro game systems generate colors in some variant of RGB encoding. But the raw pixel colors are often designed for very different screens than those that emulators typically run on. In this article, I’ll walk through the importance of color emulation, and provide some example code and screenshots.

The most common target display type these days are LCD panels. These are known for having very poor black levels. The distinction between TN, PVA, and IPS does not factor too much into this.

Sometimes CRTs are used by enthusiasts, and OLED screens, especially on phones and tablets, are slowly becoming a thing. But for this article, the focus will be primarily on LCDs, though this technique is important for all display types.

Color precision

The first detail is that most computer monitors run in 24-bit color mode, which provides 8-bits of color detail for the red, green, and blue channels. But most older game systems do not specify colors in that precision.

For instance, the Sega Genesis encodes 9-bit colors, giving 3-bits per channel.

The most naive emulator might simply place the 3-bits into the highest 3-bits of the output, leaving the low 5-bits clear, but this would cause whites to become slightly gray.

Example:

000 000 000 -> 000'00000 000'00000 000'00000

111 111 111 -> 111'00000 111'00000 111'00000

If ones were instead filled in, then blacks would become too light.

Example:

000 000 000 -> 000'11111 000'11111 000'11111

111 111 111 -> 111'11111 111'11111 111'11111

The solution to this is that the source bits should repeat to fill in all of the target bits.

Example:

000 -> 000 000 00...

010 -> 010 010 01...

011 -> 011 011 01...

111 -> 111 111 11...

In code form:

uint8 red = r << 5 | r << 2 | r >> 1

//rrr00000 | 000rrr00 | 000000rr -> rrrrrrrr

Screen emulation

Retro game systems weren’t designed to run on modern PC LCD monitors. Typically home consoles were designed for CRTs, and portable consoles using much older, much less precise LCD panels.

Emulating specific screen artifacts such as screen curvature, scanlines, color bleed, interframe blending, aperture grilles, etc are beyond the scope of this article: we are focusing only on the individual pixel colors for now.

PC monitors

There’s a fairly wide range of colors on existing monitors, as few are professionally calibrated to any kind of standard like SRGB, but in general the best we can do is to attempt to emulate colors as if one were using a properly calibrated SRGB monitor.

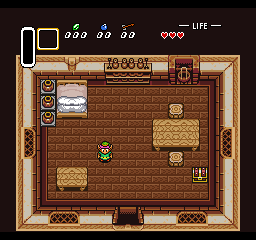

CRT emulation: Super Nintendo

The main difference between CRTs and PC LCD monitors is the substantially reduced black levels, which can only be compensated for slightly through the use of a gamma curve:

//SNES colors are in RGB555 format, so there are 32 levels for each channel

static const uint8 gammaRamp[32] = {

0x00, 0x01, 0x03, 0x06, 0x0a, 0x0f, 0x15, 0x1c,

0x24, 0x2d, 0x37, 0x42, 0x4e, 0x5b, 0x69, 0x78,

0x88, 0x90, 0x98, 0xa0, 0xa8, 0xb0, 0xb8, 0xc0,

0xc8, 0xd0, 0xd8, 0xe0, 0xe8, 0xf0, 0xf8, 0xff,

};

Originally, this table comes from Overload of Super Sleuth / Kindred fame. What it does is darken the lower half of the color palette, while leaving the upper half of the palette alone.

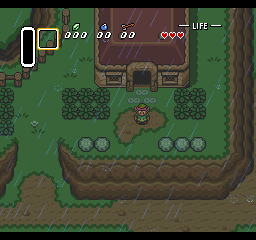

The effect on the image output from emulation is striking: the left is the original, and the right is with the gamma ramp applied:

LCD emulation: Game Boy Advance

The Game Boy Advance has one of the worst LCD screens, with colors that are completely washed out. Clever developers found that by greatly exaggerating the colors, they could produce better results on the real hardware.

Of course, if you use those colors on a standard PC monitor, the result is a technicolor nightmare. Thankfully, we can compensate for this as well to produce rather natural colors:

double lcdGamma = 4.0, outGamma = 2.2;

double lb = pow(B / 31.0, lcdGamma);

double lg = pow(G / 31.0, lcdGamma);

double lr = pow(R / 31.0, lcdGamma);

r = pow(( 0 * lb + 50 * lg + 255 * lr) / 255, 1 / outGamma) * (0xffff * 255 / 280);

g = pow(( 30 * lb + 230 * lg + 10 * lr) / 255, 1 / outGamma) * (0xffff * 255 / 280);

b = pow((220 * lb + 10 * lg + 50 * lr) / 255, 1 / outGamma) * (0xffff * 255 / 280);

This bit of code is courtesy of Talarubi.

Far more dramatic than the CRT example, the left is the original, and the right is the color-corrected version:

LCD emulation: Game Boy Color

The Game Boy Color’s screen was surprisingly better at color reproduction, and the result was only a slight bit of washing out of the colors.

An algorithm that is quite popular with Game Boy Color emulators is as follows:

R = (r * 26 + g * 4 + b * 2);

G = ( g * 24 + b * 8);

B = (r * 6 + g * 4 + b * 22);

R = min(960, R) >> 2;

G = min(960, G) >> 2;

B = min(960, B) >> 2;

Regrettably, I do not know who devised this algorithm. If you know, please contact me so that I can add proper accreditation here!

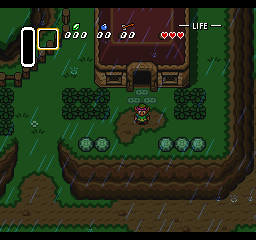

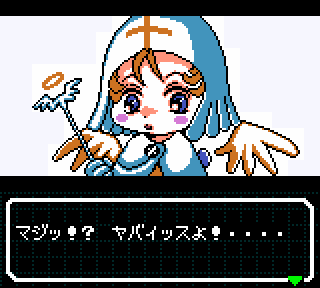

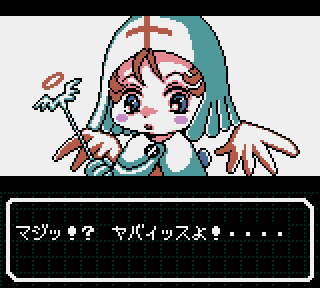

As before, the original is on the left, and the color-corrected version is on the right:

This example was chosen specifically because even though the former looks more vibrant and preferrable, if you look closely, you can see a checkerboard pattern around the character sprite that is brighter than the background.

This was likely an oversight on the part of the developers, as on a real Game Boy Color, whites are washed out and the two differing color shades blur together almost seamlessly.

Closing

There are many more systems that currently lack good color emulation filters. They’re very difficult to fine-tune. Most notably, we don’t have good filters for approximating the colors of the WonderSwan and Neo Geo Pocket at the time of writing.

Handhelds are even trickier on account of often missing backlighting (or even frontlighting in some cases!), and system controls for adjusting the contrast ratio resulting in there not being any one true “color” value for any given RGB value.

A particularly interesting corner case is the WonderSwan Color, which has a software-assignable flag to provide a stronger contrast on the image output. It’s currently not known how to emulate that precisely, or if we even really can.

Color emulation is definitely an area that could use more attention, so if you’re an expert with math and analyzing colors, it would be a great place to get involved in the emulation scene with!