The State of Emulation, Part V

(originally published by byuu on: 2019-11-13)

Every few years, I like to write about the overall progress in SNES emulation.

It’s been a long fifteen-year journey, but I believe that we have now finally reached a respectable state for SNES hardware and game preservation. Nothing will ever be perfect of course, meaning there will always be room for further improvement, but we have now reached a point where the differences between various real SNES systems isn’t much lesser than the differences between any given hardware console and the state of the art in SNES emulation.

higan

As a recap, part IV ended on a rather somber note: the burden of emulating increasingly cost-prohibitive edge cases and hardware configurations led to higan becoming very difficult and demanding to use. Since that time, that predicted trajectory mostly ended up being correct, and despite near-daily work, higan hasn’t had a stable release in two years now.

To be fair, part of higan’s complexity comes from it being a multi-system emulator: the demands of more and more emulated systems continue to add edge-cases that are extremely difficult to represent in a unified standalone emulator. Recent additions since the last article include Sega CD, Famicom Disk System, Neo Geo Pocket, MSX, SG-1000, and ColecoVision emulation.

While I am hopeful that a new higan release is finally nearing possibility, it will be perhaps the most challenging redesign to date:

The traditional user interface has been replaced with a new tree-based design: the idea is to represent every possible setting and port as a tree, allowing other nodes to dynamically connect to said ports, exposing yet more branches and leaves.

Imagine you have a Sega Genesis, and you want to connect a Game Genie to that. And then the Sonic & Knuckles lock-on cartridge to that. And finally, Sonic 3 to that. Having a “File -> Open ROM” dialog for that doesn’t really work.

Or let’s say you have an MSX2 and want to configure the system to use a RAM expansion in the secondary cartridge slot, and you want to boot your game from the attached floppy disk drive.

Or let’s say you have a Super Nintendo, and want to connect a Super Multitap four-player adapter to the second controller port, and then connect three Twin Tap controllers to it, and just to be evil, a Super Scope to the fourth controller port. Only the buttons on it would work, but hey, you could.

And when it comes to emulator coprocessor firmware, it’s yet more complexity that few want to deal with when using an emulator.

After years of struggling with every edge case being a minor existential crisis, I opted to strip all concepts out of the core emulation, and allow any system to expand itself in any way it needed to. The result is an emulator unlike any other, but it gives me the flexibility to potentially emulate anything: I could even provide an interface for exotic controllers that exist such as an exercise bike, a golf club, a barcode scanner, a fish sonar detector, etc. It may not be remotely practical to control the device from a keyboard or GUI, but it shifts the burden from the emulation core onto the GUI, so theoretically, if one day someone happened to have say a barcode reader, they could connect it up without having to emulate the underlying hardware.

SNES Emulation

Back to the topic of SNES emulation, things have gone very well since the last article.

SA-1 Emulation

In the previous article, I lamented that the system requirements of proper bus conflict emulation of the SA-1 coprocessor (used by games such as Super Mario RPG and Kirby’s Dream Land 3) would be too much for processors of the time.

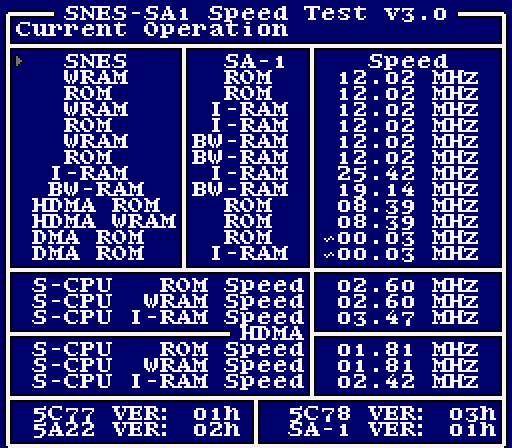

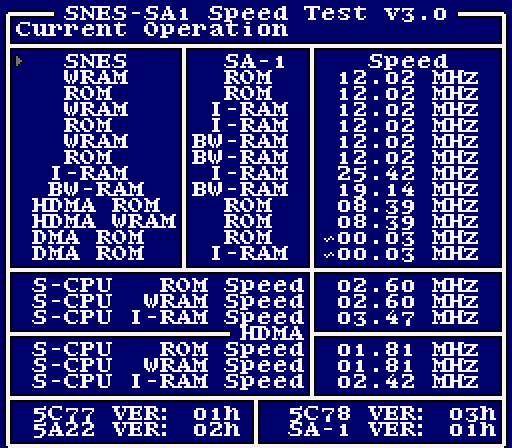

Since the article was written, Vitor Vilela created the SNES speed test suite which measured SA-1 bus conflict timings, revealing what we already knew: our emulation timings were all way off.

Test ROMs seem to be a good way to motivate me, and so I decided to attempt emulating the bus conflict delays anyway, performance be damned. In the end, I was able to get timings that are ~99% accurate, at roughly a ~20% performance penalty. Far, far less than I had pessimistically presumed back in 2016.

However, 20% additional overhead with higan is indeed a tall order: these days, higan can struggle with anything below a top-end CPU.

PPU Emulation

Another major improvement since the previous article is to PPU emulation. The PPUs are the video chips in the SNES that produce graphics. A newly remodeled cycle-based PPU now supports timings that should very closely match how the real hardware performed.

Although we still do not have any public documentation of these chips from logic analyzers, it has proven fruitful to analyze the memory bandwidth capabilities of the PPUs, and together with more test ROMs, uncover the original behavior to emulate fairly precisely.

It took some rather nasty C++ template abuse, but I was able to achieve this without any further impact to performance.

Serialization

Finally, the last major change from 2016 is the addition of truly deterministic save states.

higan has always used cooperative threading for processor synchronization, which has traditionally made serialization, or save states, a very complicated issue to solve.

After many years, I was finally able to come up with a new method for deterministic cooperative thread serialization.

This is very important, as the old model had an infinitesimal chance of failing to properly serialize and deserialize the SNES state, which limited higan to only being able to offer standard save states and no additional functionality.

Dynamic Rate Control

Not directly related to core emulation, but for the user experience, I was finally able to implement working dynamic rate control support. Essentially this means that my emulators can maintain smooth video and audio at the same time, without ever having the screen stutter or tear, or having the audio periodically crackle.

bsnes

I mentioned at the start of the article that things have been looking up as of late, and that is largely due to the revival of the bsnes project.

Essentially, back in 2004, my first emulator was for the SNES. As it continued to support more and more systems (spurred on by Super Game Boy emulation), the name increasingly failed to make much sense, and so the project was renamed to higan.

Contrary to popular opinion, I’ve never really been a hard-liner against easy-to-use emulator interfaces, performance-focused software, and emulator enhancements. I’ve even come around in recent years on supporting abandoned legacy homebrew software, designed using older emulators, that doesn’t even run on real hardware.

The problem is that these niceties are extremely difficult to co-exist within an emulator that is focused on accuracy: speed hacks get in the way and need to be constantly maintained, ease-of-use features dictate the omission of supporting certain edge cases (say, the Super Multitap example above), and this all takes time away from the goal of trying to improve emulation accuracy. The enhancements actually make the task more difficult by getting in the way of the code serving as a form of verifiable hardware documentation.

But with the above SNES emulation improvements, I felt that SNES emulation was finally complete enough to warrant a hard-fork of higan, and I chose to reuse the existing bsnes branding for this.

bsnes today serves as a pure SNES emulator (with Super Game Boy support, of course), which focuses on performance, features, and ease-of-use.

It may be a bit of a departure from the usual theme of ‘State of Emulation’ articles, but I’ll cover some of the major milestones seen in bsnes below.

Multi-Threaded PPU Renderer

Given that the SNES locks video RAM during active display, I came up with an observation around the caching of video register settings that has allowed me to successfully parallelize the SNES video renderer, allowing a significant performance improvement over even traditional scanline renderers found in other SNES emulators.

HD Mode 7

Unbeknownst to me at the time, it would turn out that having the state of every scanline available before rendering the first would allow for upscaling SNES mode 7 (affine texture scaled and zoomed) graphics to basically any resolution. Given the internal mode 7 texture size is 1024×1024, there’s a lot of detail there to work with, allowing for probably the most phenomenal-looking enhancement ever in SNES emulation: HD mode 7.

All credit goes to DerKoun for seeing the potential everyone else missed, and implementing it into bsnes.

Widescreen Support

Although this isn’t ready yet, a future enhancement I am greatly looking forward to adding to bsnes is 16:9 widescreen support for games.

The tilemaps and coordinate system for the SNES PPU easily allows for this, but in order for it to function properly, games will have to be manually patched to support the additional screen space.

It’s basically a waiting game in the hopes the idealized (and real!) screenshots such as above will convince SNES ROM hackers to create these patches. If and when they do, my hope is to bundle them with bsnes to allow for automatic widescreen support out of the box.

Overclocking

Taking a technique from the NES emulation scene, we now have an overclocking method involving the insertion of additional scanlines during the vertical blanking period that allows for very stable overclocking of the SNES processors, which eliminates lag in virtually any game that has it.

Run-Ahead

Thanks to the new cooperative serialization method, run-ahead support became possible. Run-ahead is a truly magical technique that can remove entire frames of internal input latency from games. With a good setup, software emulation is now capable of achieving less input latency than original hardware!!

The Future is Bright

With the combination of HD mode 7, widescreen, overclocking, run-ahead, and all of the other new features, “not an emulator” is no longer a selling point.

SNES emulation has truly come into its own. And with everything well-documented, we’re seeing more and more new interest in SNES emulator development.

SNES Preservation Project

As much as I’d like to forget the experience, this article wouldn’t be complete without mentioning the disastrous shipping debacle that almost completely derailed the SNES preservation project.

A package containing 100 PAL SNES games got lost for nearly six months before finally being delivered. The games were preserved and returned to their owner.

I’ve since moved to Japan which has resulted in a hold on this project, but it’s still very much a goal of mine: the USA collection has already been completed, I have the full Japanese collection but I am only around 10% of the way through preserving it, and the European collection is approximately 50% preserved already.

To recap, this project has found several bad dumps and several new revisions, and has resulted in substantial memory mapping emulation improvements. It also remains the most expensive undertaking of my life, but hey, you only live once!